Thursday, October 27, 2011

The Ides of March

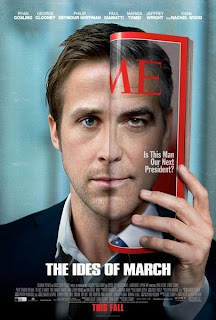

George Clooney has tried his hand at directing again with The Ides of March. Based on the 2008 play, Farragut North by Beau Willimon, the name was fittingly changed to reflect Ceasar’s days of betrayal as well as Shakespeare’s great work Julius Caesar. Clever Clooney puts many literary allusions to work. The plot, in short, focuses on a political race for the democratic seat where the real players are the men behind the scenes calling all the shots. On a larger scale, the film is a psychological drama set in a political arena that revolves around thematic ideals of loyalty and allegiance - but at what cost to individual honor? The opening scene shows Stephen, the young campaign manager played by Gosling, as he checks the stage and microphone for the Governor’s (Clooney) debate already suggesting that he is the puppet master. The film continues with the fight for the democratic seat, as the moral ambiguity of the central characters (played by Gosling, Clooney, Hoffman and Giamatti – all finely acted, we already know they are good at their craft) creates a thrilling power struggle until the end. It also makes us question who the good guy is and who the bad guy is as ideals and allegiances change.

The film contains realistic character studies of people in the political realm which will strike close to home with the upcoming elections in Washington. Aside from the political jargon that might float over your head, Clooney and his team did a great job with the script adaptation and dramatic dialogue. But the climax of the film that shifts the choice and path of the characters has holes. The intern, a title that already makes one think “sex scandal,” played by Evan Rachel Wood, lacks character development. Her eventual situation with the governor and tragic demise (however Ophelia-esque it might be, since Clooney is clearly thinking of Shakespeare) lacks credibility. We don’t know enough about her past to make her actions realistic, which unfortunately leads to plot holes, and takes away from the film at a pivotal moment.

The visuals and camera work border on corny, and Phedon Papamichael’s cinematography plays it safe. The camera lingers too long on Gosling silhouetted by the giant American flag that takes up the screen. In another emotional moment, he cries as the rain beats down on the windshield. The lack of subtlety leaves nothing to the imagination. However, I did like the close ups on intimate conversations. For example, the shot of Gosling and Wood flirting in the bar draws us in and suggests the secrecy of politics in general; the framing is suggestive and dangerous. The musical score creates a jarring turn that reflects the anger and revenge Gosling feels towards the Governor. But other musical moments, for example the random jazz song that gets too much camera time in the bar, seem out of place and without reason.

At the end of the film Gosling confronts Clooney in the shadowed kitchen of a closed restaurant – an almost mafia moment – where he proclaims “you don’t fuck the intern.” This political cloak and dagger again alludes to Shakespeare’s play and shifts the power back to Gosling. For him, the end will justify the means even if it calls for blackmail. The final shot is a slow zoom to an extreme close up on Goslings face, with his ear piece, as the face of the governor’s campaign. He now has all the power, but we are left to wonder what he will do with it.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Garage Projects - film screening Friday night

What: Film screening - BRANDED TO KILL (Suzuki, 1967)

When: 8 PM, Friday Oct. 14

Where: Castleberry Hill - Garage Projects- 261 Peters St.

Spread the word!

http://garageprojects.blogspot.com/view/classic

Sunday, October 9, 2011

Johnny Guitar- Oct. 11 on TCM at 10 PM

Set your DVR for an amazing post-war Western on Turner Classic Movies. Johnny Guitar (Nicolas Ray, 1954) is the focus of my 2010 Master's thesis. I've included an excerpt of my paper below.

Women Take the Reins: Star, Social Discourse, and the Duality of Readership in the 1950s Western

from page 20... a passage on the actions and dress of the female characters in Johnny Guitar and The Furies (Anthony Mann, 1950)

The masculine positioning of Crawford in Johnny Guitar also suggests her sexual confidence over men. Her ability to function within the masculine geography of the western creates a unique character that can function as both male and female. When Vienna first appears onscreen, one of her employees makes a comment about Johnny Guitar: “That’s a lot of man your carrying in those boots stranger.” Interestingly, this comment is off-screen while the camera lingers over Vienna. Jennifer Peterson argues that, “Despite her gender – or more accurately because her gender is not static but floating, both ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ – Vienna is allowed to stand as a self-sufficient individualistic western hero.”[1] However, by allowing Vienna to function as a man, problems arise that question Vienna’s moral ambiguity. She is unfulfilled in her role of female and is obsessed with positing herself as a man. Ray adeptly acknowledges this with Vienna’s stance – legs always spread apart counter to a feminine stance, with a gun strapped to her leg. This illustrates Vienna’s phallic lust for power that is thwarted by the end of the film.

Women Take the Reins: Star, Social Discourse, and the Duality of Readership in the 1950s Western

from page 20... a passage on the actions and dress of the female characters in Johnny Guitar and The Furies (Anthony Mann, 1950)

The masculine positioning of Crawford in Johnny Guitar also suggests her sexual confidence over men. Her ability to function within the masculine geography of the western creates a unique character that can function as both male and female. When Vienna first appears onscreen, one of her employees makes a comment about Johnny Guitar: “That’s a lot of man your carrying in those boots stranger.” Interestingly, this comment is off-screen while the camera lingers over Vienna. Jennifer Peterson argues that, “Despite her gender – or more accurately because her gender is not static but floating, both ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ – Vienna is allowed to stand as a self-sufficient individualistic western hero.”[1] However, by allowing Vienna to function as a man, problems arise that question Vienna’s moral ambiguity. She is unfulfilled in her role of female and is obsessed with positing herself as a man. Ray adeptly acknowledges this with Vienna’s stance – legs always spread apart counter to a feminine stance, with a gun strapped to her leg. This illustrates Vienna’s phallic lust for power that is thwarted by the end of the film.

Figures 3 - Vienna in position of power

The traditionally masculine garb is more noticeable when juxtaposed to the heroines’ feminine costumes. For example, Vienna dons a luminous white dress with a layered skirt and puffy sleeves when she closes her saloon. Similarly, we first see Vance in her deceased mother’s ball gown trying on jewelry. These images of excessive femininity serve to call attention to the alternative masculine costumes, calling the viewers attention to the power that has been given to the female. The costumes serve both types of readership. Importantly, even while these women are in feminine dress, they still possess authority and strength. The dimorphic costumes of both Vienna and Vance suggest mobility between male and female spheres. On the one hand, Vance is a daughter and Vienna was a prostitute, but they now assume roles as businesswomen as their formal pants would suggest. With these costumes they move into the male position in the western.

[1] Jennifer Peterson. “The Competing Tunes of Johnny Guitar: Liberalism, Sexuality, and Masquerade.” The Western Reader. Ed. Jim Kitses, Gregg Rickman. Limelight Editions. New York. 1998. p. 331.

Monday, October 3, 2011

Moneyball

I'm not a huge baseball fan. In fact, I find it uninteresting, boring even. That being said, Moneyball is charming. Brad Pitt and Johan Hill lead as Billy and Peter, two men using an unorthodox method to change the game of baseball for the Oakland A’s. These two actors captivate the audience; Hill with his subtle shyness and unassuming intelligence, Pitt with his emotionally charged relationship with the game of baseball and the past decisions that haunt him in the form of flashbacks.

Typically the classic narrative of “losing team rises to stardom against all odds” would translate as stale and clichéd. However, the story of Moneyball rings true and fresh. The direction of Bennett Miller, who also directed Capote in 2005, is superb as he creates silences that speak more than any dialogue in the film. The evocative performances of Pitt and Hill are tangible, tense at times, and truly draw the viewer into the story. Aaron Sorkin, now a household name due to The Social Network, co-wrote the adapted screenplay based on Michael Lewis’s book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game. Sorkin again creates an unforgettable story.

The majority of the film explores Billy’s relationship with the game of baseball. He mentions that baseball is truly romantic. The film points to the fact that major league players are paid so much that some of the romance has been taken out of the game. For Billy and Peter, they have a miniscule budget which doesn’t allow them to pay the 12 million dollar salaries, so they work with what they can afford based on the statistics of each player. With this new form of recruiting and managing, Billy’s relationship with the game changes, and a new type of baseball is born.

Visually, the film is pretty standard and unfortunately lacks ingenuity. The only point of deviation from classic editing seems to be the abstract charts and numbers that pixilate across the screen as Peter goes through stats and figures with Billy. But where the film lacks visually, it is made up in the writing and acting.

Throughout the film we question what drives Billy. Is it trying to fulfill the baseball career he never had after high school? Is he trying to right the fact that the scouts were wrong about him? And then there is a young daughter who is prevalent in his life that fuels many of his decisions and ultimately his final one. Peter’s metaphor of Billy “hitting a home run” at the end of the film reads a bit sappy, but overall the poignancy of the film is on point and worth sitting through the extra innings.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)